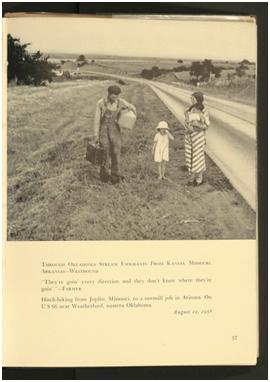

What I really respect about Lange is that she went in with the idea of telling these people’s stories, hence the work she did with husband Taylor is one of the first instances I can find where images are systematically displayed alongside first-hand testimony that speaks of the why and wherefore behind or related to the visual.

They also used official testimony from the presidential committee and other government sources:

“The Committee’s examination of the agricultural ladder has indicated an increasing tendency for the rungs of the ladder to become bars – forcing imprisonment in a fixed social status from which it is increasingly difficult to escape.” President’s Committee on Farm Tenancy.

The rationale was to explore the people’s experiences and document them, juxtaposing feelings on the ground with administrative policies. The logical leap was left to the audience. In a way this was empowerment before the notion had even taken hold.

Since Taylor was an agricultural economist, he was probably more interested in understanding the views and opinions of the farmers and sharecroppers so as to more effectively change their opinions and behaviours. The point is that coming at a project from a point of view other than purely photographic is always a bonus. (Salgado another case in point)

The genuine voices of the people are heard, without commentary and without judgement, speaking to the couple directly or overheard at the time they were being photographed. The quote is part of the image and not a caption (as in a directional tool) so much as an added dimension. This is a vital distinction. As Beaumont Newhall says of this collaborative project, it is “fully documentary in spirit” (1949, p 183). William Stott also remarked:

“Documentary photography, as Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor explained in 1939, rested “upon a tripod of photographs, captions, and text” the single intention of which was to let the subjects, the “living participants” of a social reality, “speak to you face to face.” Having looked at a documentary book, “you” could no longer be ignorant of them. You had seen their faces” (Stott 1986, p 214).

I like the analogy of the tripod; a triad of forces, each one supplementing and supporting the other. In contrast to Evans’ and Agee’s work, this volume had a clear political message, as Shelley Rice points out:

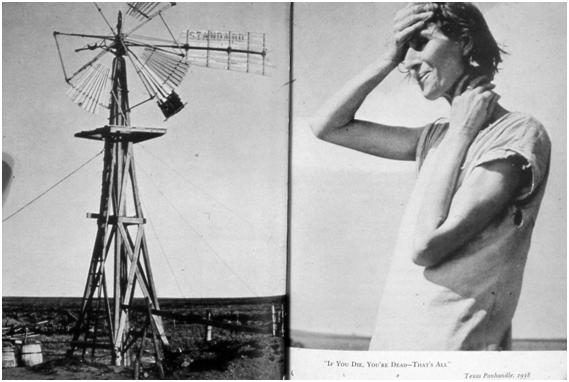

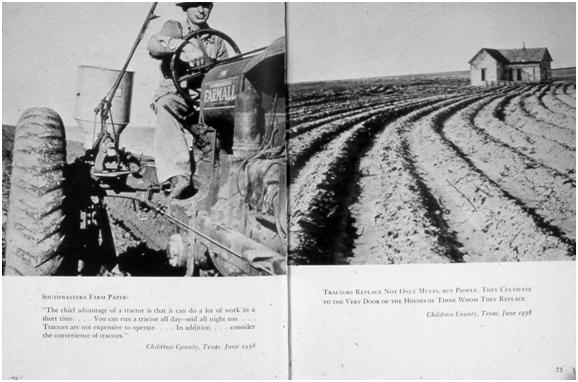

“Lange’s photographs emphasize the strength of the migrants forced to grapple with overwhelming challenges – challenges created not by the people themselves but by the impersonal workings of an agricultural and industrial system that is destroying the natural and human resources of our nation” (2001, p 18).

Although this version is in fact slightly at odds with the views of RA director Rexford Tugwell, who believed it was the farmers themselves who were to blame for the mismanagement of the land.

On the other hand, Lange has also been accused of exploiting her subjects, in particular Florence Thompson or the Migrant

Mother who, in an LA Times article, ‘Can’t Get a

Penny‘ was quoted as saying: “That’s my picture hanging all over the world, and I can’t get a penny out of it.” The article went on:

“Mrs. Thompson claims she has been exploited for the last 42 years. “I didn’t get anything out of it. I wish she hadn’t of taken my picture,” the full-blooded Cherokee Indian said. “She didn’t ask my name,” Mrs. Thompson added. “She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.” . . . Mrs Thompson said she is proud to be the subject of such a famous photograph, “but what good’s it doing me?“” (L.A. Times November 18, 1978, quoted in Gross et al 1988, p 14).

Informed consent? Once again, Lange obviously felt that there were larger concerns at stake than Ms Thompson’s privacy – after all, the woman had cooperated and not refused to be photographed. It has also been reported that after the photograph was published, the government did respond directly by sending 20,000 lbs of food aid to the camp where Thompson was photographed.